PENDING EXTERNAL REVIEW Key Facts

- Beef products are widely consumed and play an important role in the U.S. food system.

- The U.S. cattle inventory (as of April 2024) was 87.2 million

- More than 50 percent of the total value of U.S. sales of cattle and calves comes from five states: Texas, Nebraska, Kansas, California, and Oklahoma.

- The average consumption of beef in the U.S. is 57.2 pounds per year.

- The U.S. is a top exporter of beef, with its top markets being Canada, Japan, Mexico, South Korea, and Hong Kong.

- Between 2000 and 2020, at least 906 beef-associated outbreaks were reported to CDC’s National Outbreak Reporting System (NORS), causing 18,155 illnesses, 1,258 hospitalizations, and 21 deaths.

- The two most recent fresh beef-related recalls occurred in 2019 due contamination of Salmonella Dublin and Escherichia coli (E. coli) O103 which has completed.

- Foodborne pathogens most commonly associated with beef products include STEC (shiga-toxin producing Escherichia coli) and Salmonella; improper handling and cooking have been identified as key causes of foodborne illness associated with beef products.

PENDING EXTERNAL REVIEW Contents

Introduction

Beef cattle were first introduced to America by European colonists, but the industry did not experience widespread growth until the 1800s with the advent of refrigerated rail cars. The term beef refers to meat from full-grown cattle around two years of age, weighing between 1000 and 1300 pounds, and yielding approximately 450 to 600 pounds of edible red meat. The safety of the beef supply has been a focus of U.S. regulatory agencies for over 100 years. The Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS) is required by law to provide inspection for all federally-regulated beef establishments. Without an inspector present, the establishment cannot process cattle for human consumption. All beef sold in retail stores has been inspected for wholesomeness by the USDA or another state health agency and carries the “Passed and Inspected by USDA” emblem.

Foodborne Outbreaks and Recalls

Agricultural animals are reservoirs for several foodborne pathogens and have a major role in their spread through food and water supplies from contact with contaminated manure. High prevalence of these pathogens is common in areas where contamination is continuous, namely farms, transportation trucks used to deliver animals, and slaughtering facilities. Between 1998 and 2018, at least 1,078 beef-associated outbreaks were reported to CDC’s National Outbreak Reporting System (NORS), causing 22,013 illnesses, 1,329 hospitalizations, and 22 deaths. The most common pathogens include Escherichia coli O157:H7, non-O157 shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC), and Salmonella. CDC has reported multistate outbreaks of E. coli O157:H7 infections linked to beef products in 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2014; Salmonella Typhimurium infections associated with ground beef in 2011 and 2013, Salmonella Enteritidis associated with ground beef in 2012.

One of the most devastating and well-known E.Coli O157 outbreaks was associated with the hamburgers from the Jack-In-The-Box fast food chain. Over 70 Jack-in-the-Box locations were linked to this outbreak leading to over 700 people across four states falling ill. Investigation into the outbreak connected the outbreak to five slaughterhouse facilities. Although these bacteria are destroyed by proper cooking, illnesses may result from improper handling or cooking. Good management practices during pre-harvest and processing can reduce the prevalence of foodborne pathogens associated with fresh beef products.

From August of 2019 to October of 2019, there were 13 reported cases of Salmonella Dublin including 9 hospitalizations, and 1 death in 8 different states. Central Valley Meat Co. in Hanford, California, recalled 34,222 lbs of ground beef products that were potentially contaminated with Salmonella Dublin. Since this outbreak, several additional multistate outbreaks have occurred due to contaminated beef products. A large outbreak of Salmonella Newport spanning 30 states began in August 2018 and lasted until February of 2019, infecting 403 individuals and leading to 117 reported hospitalizations. Investigation into the outbreak found that 83% of ill people reported consumed ground beef at home in the week leading up to illness, and collection of ground beef from ill persons’ homes identified the Salmonella Newport outbreak strain. The source of the ground beef was traced to JBS Tolleson, Inc., who consequently issued two recalls in October and December of 2018 that totaled to over 12 million pounds of beef products.

A second outbreak associated with beef products occurred in the several months following in March to May 2019. A total of 209 individuals were infected across 10 states, with 29 cases leading to hospitalization and two cases of hemolytic uremic syndrome. DNA fingerprinting identified the outbreak strain as Shiga toxin-producing E. coli O103. Both epidemiological and laboratory evidence identified ground beef as the likely source of the outbreak, wherein 79% of interviewed ill persons reported consuming ground beef purchased at grocery stores, restaurants, or other institutions. No single supplier of ground beef products was identified that accounted for all illnesses, ultimately leading to two companies issuing recalls; Grand Park Packing in Franklin Park, Illinois issued a recall of 53,200 lbs. and K2D Foods in Carrollton, Georgia recalled 113,424 lbs.

Production

(Pre-Harvest)

Although proper cooking can eradicate foodborne illness pathogens, the more control points the beef industry implements, the lower the risk of carcass contamination during slaughter and processing. Implementing these practices on the farm and in the feedlot is the most cost-effective way to reduce prevalence. The contamination cycle starts when animals ingest food or water contaminated with feces, so feedbunks and water tanks are cleaned frequently at feedlots to help control pathogen contamination. Stresses on animals contribute to animals shedding pathogens; therefore, implementation of low-stress equipment and practices have become common practice at feedlots. Other pre-harvest interventions implemented include the use of direct fed microbials (DFM), microphages, and vaccinations. The DFM serve as a probiotic to help reduce incidence of pathogenic E. coli. Microphages are selected to target certain pathogens and invade and destroy bacteria, both in animals and in the feedlot environment. Some success has been reported with vaccines targeted to help reduce incidence of pathogenic E. coli and Salmonella. The intervention strategies at the farm level will never eliminate pathogen concern; however, having an understanding of the on-farm sources of infection helps with better control of pathogens.

At any point where fecal contamination may come in contact with other animals or even common objects such as fences, walls, or trailers, surfaces are commonly sanitized to maintain cleanliness and prevent cross-contamination. This includes transportation to the processing facility and in the holding pens once the cattle have been unloaded. At many processing facilities, a pre-harvest cattle wash is implemented to reduce fecal matter that could enter the facility on the hides of the animals. Along with the concern of foodborne pathogen contamination, animals are also evaluated to ensure they are fit to be slaughtered. The Federal Meat Inspection Act requires USDA to provide inspection of all live animals before entering the slaughter establishment to ensure animals are healthy and fit for slaughter. If animals are sick or have an injury, the USDA inspector will deem them as unfit for human consumption, and those animals will not enter the food supply.

Production (Post-Harvest)

Hide-On Food Safety Control

Skeletal muscle from healthy cattle has generally been considered sterile prior to slaughter, with the exception of lymph nodes. Hides are a primary source of bacterial contamination on beef carcasses and can carry contamination through the whole production process if not addressed and controlled.

Beef cattle are humanely stunned and rendered unconscious/insensible before the exsanguination process (removal of blood). Because the hide is considered a contaminated exterior surface, two knives are used to exsanguinate the beef carcasses. In order to avoid cross-contamination with the exterior of the hide via the knife, one knife is used to cut through the hide and another sterilized knife is used to sever the arteries within the sterile interior of the carcass (knives are sterilized between carcasses).

After the beef carcasses have undergone the exsanguination step, several food safety intervention options may be utilized to decontaminate the hide before it is removed from the carcass. This helps prevent cross-contamination of the sterile exterior of the hide-off carcass. Some processors will use a hot water wash designed to rinse and scrub dirt and fecal material from the exterior of the hide along with some thermal destruction of bacteria. Chemicals, such as trisodium phosphate, chlorine, or acidified chlorine may also be used to decontaminate hides. Once the hide is clean, the process of removing the hide begins.

Hide Removal

Hide removal is the most time-consuming and intricate step in the beef slaughter process, as there are multiple steps conducted to prevent contamination of the internal carcass. Removal begins with a knife used at the hocks and midlines, and knife sterilization is key to preventing contamination. Preventative measures, such as placing paper on the inside flaps of hides to prevent them from swinging and touching the outside surface of clean carcasses, are small steps that can have a large impact in preventing contamination of the carcasses. The initial opening of the hide is often trimmed to remove the exterior pieces of tissue that may have come in contact with the hide. Steam vacuuming is also used to decontaminate the limb removal sites at the hocks and shanks. Organic acids (lactic acid or citric acid) may be applied to the midline of the ventral (under) side of the beef carcasses before the peritoneal (internal) cavity of the carcass is opened for evisceration (removal of viscera/organs).

Pre-evisceration and Evisceration

Many processors have pre-evisceration food safety interventions in place before the removal of the visceral organs takes place. This often includes an organic acid spray and/or a hot water wash, which helps to ensure decontamination of bacteria that may have occurred during the hide removal and before the evisceration process. Good manufacturing practices (GMP) must be in place for the removal of the viscera. It is imperative that no breakage of the rumen or intestines occurs, which could cause contamination of the carcass. Knives are sterilized between processing each carcass to avoid cross-contamination.

Zero Tolerance

A 1993 outbreak of E. coli O157:H7 associated with undercooked ground beef patties served at a fast food chain resulted in USDA-FSIS implementing a Zero Tolerance standard. This mandated no tolerance for visible fecal, milk, or ingesta on the beef carcasses. It must be excised or trimmed away from the carcasses to prevent contamination.

Final Carcass Interventions

After all processing steps for preparing the beef carcass are complete, there are typically a series of interventions before the carcass enters the cooler. Multiple hurdle technology is the most effective method for controlling the risk of pathogens in meat and poultry products both pre and post-harvest. Post-harvest interventions, both physical and chemical, are the most effective interventions used in plants today. These interventions may include chilling, carcass washes, steam pasteurization, hot water pasteurization, and chemical treatments (as sprays and immersions). Typically, beef carcasses undergo tested pathogen reduction interventions such as hot water pasteurization or steam pasteurization, followed by treatment with an antimicrobial acid spray, before entering the cooler for chilling.

Spray Chilling

Beef carcasses are chilled in carcass coolers for approximately 24 hours following harvest, typically using spray-chilling methods. Carcasses are chilled with refrigeration and cold water to help drop the temperature of the carcasses rapidly to prevent growth of microorganisms. The water helps aid in the chilling process and can serve as an antimicrobial intervention wash with low-concentration acids to hinder bacteria growth.

Fabrication

After the carcasses are properly chilled, the fabrication process begins (disassembling the carcass into wholesale and retail cuts). This process is done on sanitary surfaces with sterilized equipment. Employees cutting beef have knife sterilizers and appropriate GMP dress while processing the beef products—first into primal and sub-primal cuts and then into saleable products (i.e., roast, steaks, etc.). During this process, producers use organic acid-spray cabinets to further inhibit microbial growth before the products are packaged as wholesale, retail, and trimmings destined for ground beef. Depending on customer requirements, the processor will collect samples for microbial testing to provide customers with a certificate of analysis or negative documentation for target organisms.

HACCP Monitoring and Control of Pathogenic Hazards

All USDA-FSIS federally inspected beef plants are required to implement HACCP (Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points) systems. HACCP is a systematic approach to risk assessment by identifying and controlling biological, chemical, and physical hazards associated with meat and poultry products, while providing documentation of the production of safe, wholesome, and unadulterated meat products. FSIS has increased efforts to control foodborne pathogens by increasing requirements and regulatory efforts such as Listeria monocytogenes testing and the addition of non-O157 STEC (O21, O45, O103, O111, O121, O145) to the adulterant list for ground beef products and trim. CDC has recognized that the implementation of HACCP into meat and poultry systems has contributed to a reduction in the incidence of foodborne illness overall in the United States since 1996. Each inspected beef plant has HACCP plans for their system that have undergone risk assessment and implementation of critical control points to help prevent, eliminate, and reduce biological hazards.

Sanitation and GMPs

Sanitation is an imperative pre-requisite program for a beef plant’s HACCP plan. By having clean facilities and equipment, the beef plants can successfully control bacteria. Sanitation is done with detergents and sanitizers designed for meat processing facilities to help clean fat and protein residues along with eliminating bacteria biofilms. The processing area is cleaned every night before the start of production with a complete wash down, detergent foaming, scrubbing, and multiple hot water rinses and sanitizing steps. Along with daily cleaning, programs are in place for operational sanitation procedures during the processing day to keep facilities and equipment clean.

Along with facility cleanliness, beef plants also have strict GMP programs for their employees. Common practices include requiring hair nets, frocks, gloves, rubber boots, and no wearing of jewelry, as well as procedures for proper hand washing, knife sterilization, use of boot sanitizers, and operational table clean-up.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics may be given to prevent or treat disease in cattle, but all medications given to cattle require a withdrawal period; this means animals are not given any medication for the required amount of time prior to slaughter. During the withdrawal period, residues of the medicine or antibiotics exit the animal’s system. At slaughter, random samples (typically from the kidneys) are taken by FSIS and tested for residues. Very low percentages of residue violations have been reported.

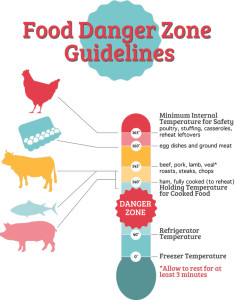

Food Safety

Many steps are in place to ensure the product at the retail level is safe for human consumption, but safe handling of meat products may not be practiced at home. When shopping, consumers should make sure that beef products are cold (< 40 °F), put in a plastic bag before placing in the grocery cart, and purchased last in order to control temperature, and avoid cross-contamination with other foods. Temperature control is extremely important with beef products prior to cooking; meat should always be properly stored and thawed. Fresh beef should be consumed within three days of purchasing or it should be frozen. Safe handling recommendations for consumers include storing meat below ready-to-eat foods in the refrigerator; thawing either in the refrigerator, microwave, or under cold running water; washing hands before and after handling meat; using clean knives and cutting boards designated for meat; and always washing utensils well in hot, soapy water after each use. Using a meat thermometer is also recommended to ensure ground beef or tenderized steaks are cooked to a minimum temperature of 160 °F and steaks and roasts are cooked to a minimum of 145°F.

Consumption

The United States is the leading global consumer of beef, consuming 21% of global beef in 2018. In 2014, Americans consumed a total of 24.1 billion pounds of beef amounting to $95 billion dollars. While the retail price of “choice” beef has steadily been increasing (current average is $5.97/lb), the overall consumption of beef has steadily decreased since 2007 (from 65 to 57.2 lb/person). In the Population Survey Atlas of Exposures 2006–2007, 46.2% of the survey cohort reported eating beef at home within the past seven days. Furthermore, 26.1% of the survey population reported eating beef outside of the home within the past seven days.

For information on how to properly store fresh beef products to ensure food safety please visit FoodKeeper App.

Nutrition

Beef is a source of complete protein as well as an excellent source of phosphorus, protein, selenium, Vitamin B12 and zinc and a good source of iron, niacin, Vitamin B6, and Riboflavin. In fact, red meat accounts for 61% of vitamin B-12 in the U.S. food supply. This nutritional powerhouse plays a role in helping with red blood cell development and preventing iron deficiencies, one of the most common nutritional deficiencies in the U.S., conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), a derivative of the essential fatty acid, linoleic acid, may potentially protect against cancer, heart disease, and diabetes and may enhance immune function. Beef accounts for approximately 36% of the total amount of CLA consumed. In addition to these health qualities, excess consumption of red meat and saturated fat have been associated with increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and other disorders. Due to these risks, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans advise consuming lean meats with lower fat content over meats with higher fat content.

References

- Arthur TM, Bosilevac JM, Nou X, Shackelford SD, Wheeler TL, Kent MP, et al. Escherichia coli O157 Prevalence and Enumeration of Aerobic Bacteria, Enterobacteriaceae, and Escherichia coli O157 at Various Steps in Commercial Beef Processing Plants. J Food Prot [Internet]. 2004;67:658–65.

- Ben A, Smith E al. A risk assessment model for Escherichia coli O157:H7 in ground beef and beef cuts in Canada: Evaluating the effects of interventions. Food Control; Science Direct [Internet]. 29(2):364–81.

- Bosilevac JM, Nou X, Osborn MS, Allen DM, Koohmaraie M. Development and Evaluation of an On-Line Hide Decontamination Procedure for Use in a Commercial Beef Processing Plant. J Food Prot [Internet]. 2005;68:265–72.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Foodborne Disease Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) Population Survey Atlas of Exposures, 2006-2007 [Internet]. Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC): U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 2006 2007 p. 16–26. (FoodNet Population Survey Atlas of Exposures).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of Salmonella Infections Linked to Ground Beef [Internet]. Salmonella. 2019 [cited 2021 Jul 14].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of E. coli Infections Linked to Ground Beef [Internet]. E. coli (Escherichia coli). 2019 [cited 2021 Jul 14].

- Elder RO, Keen JE, Siragusa GR, Barkocy-Gallagher GA, Koohmaraie M, Laegreid WW. Correlation of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 prevalence in feces, hides, and carcasses of beef cattle during processing. PNAS [Internet]. 2000;97:2999–3003.

- Graves Delmore LR, Sofos JN, Schmidt GR, Smith GC. Decontamination of Inoculated Beef with Sequential Spraying Treatments. Journal of Food Science [Internet]. 1998;63:1–4.

- Hulebak KL., Schlosser W. Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) History and Conceptual Overview. Risk Analysis [Internet]. 2002;22:547–52.

- Huffman RD. Current and future technologies for the decontamination of carcasses and fresh meat. Meat Sci [Internet]. 2002;62:285–94.

- Industry Statistics. (n.d.).

- Sofos JN. Challenges to meat safety in the 21st century. Meat Science [Internet]. 2008;78:3–13.

- Soon J.M, E al. Escherichia coli O157:H7 in beef cattle: on farm contamination and pre-slaughter control methods. Animal Health Research Reviews [Internet]. 2011;12(2):197–211.

- United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Cattle & Beef Statistics & Information [Internet]. USDA Economic Research Service. 2015.

- United States Department of Agriculture Food Safety Inspection Service. Beef from Farm to Table [Internet]. United States Department of Agriculture; Food Safety Inspection Service. 2014.

- USDA-FSIS. Verification of Procedures for Controlling Fecal Material, Ingesta, and Milk in Slaughter Operations [Internet]. Food Safety and Inspection Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2011.

- S. Department of Agriculture,. Health Benefits of Beef [Internet]. Beef Checkoff. 2002.

- Wheeler TL, Kalchayanand N, Bosilevac JM. Pre- and post-harvest interventions to reduce pathogen contamination in the U.S. beef industry. Meat Science [Internet]. 2014;98:372–82.