Externally Reviewed Key Facts

-

The FDA defines milk as “the lacteal secretion, practically free from colostrum, obtained by the complete milking of one or more healthy cows.”

- Milk is one of the most affordable highly nutritious foods.

- Milk was once a common source of food borne illness, but is now one of the safest perishable foods available.

- An average milking cow produces between 3 and 3.5 gallons per milking.

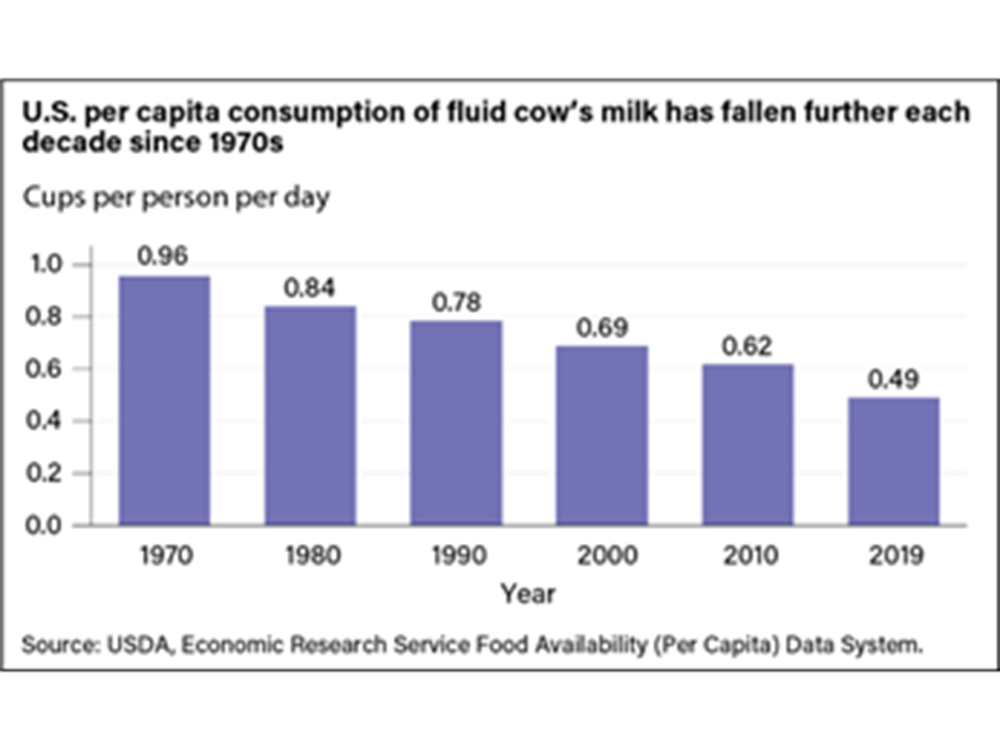

- Fluid milk consumption has been decreasing for the past two decades at an accelerated rate.

- Milk production per cow has increased by 11% between 2010-2019. The average number of cows per operation has decreased, likely due to the increase in individual production.

- Raw (unpasteurized) milk demand has risen over the past few years as consumers search for local and natural alternatives to commercially processed foods.

- In 1987 the FDA prohibited the sale of raw milk across state lines. Individual states regulate the sale of raw milk within the state’s borders.

Externally Reviewed Contents

Introduction

Whey proteins specific to cows have been found in ancient human dental calculus from Africa, indicating humans have consumed dairy since the 6th millennium BCE (1). Milk consumption may have perpetuated the human species in a similar way to agriculture as it allowed for earlier weaning and a decreased time between births (1). As some populations developed the ability to more effectively digest milk into adulthood, milk became an increasingly important food source. Cattle traveled with immigrants from Europe to the US starting in the 1600’s and were used to supplement the family food supply with beef and milk. As the US population moved off of their farms and into the city during the industrial revolution, commercial dairy farming was born (2). Today, dairy farms in the US represent a major sector of the agricultural market and are a vital part of the economy.

Americans consumed an all-time high amount of dairy in 2021, with each person averaging 667 pounds of milk products consumed that year. Milk as a stand-alone beverage has waned in popularity over the past few decades in the US, however, production of milk products like cheese, ice cream, yogurt, and coffee creamers continues to grow. Sometimes referred to as a “perfect food”, milk provides multiple nutrients in a highly digestible form. Milk is a good source of calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, and vitamin B12, as well as several complete proteins like casein and whey. Commercially marketed milk in the US is also commonly enriched with vitamin D.

Understanding Milk Quality

Grade A

All retail fluid milk (milk for drinking) is sold with a “Grade A” certification as required by law. The term “Grade A” milk signifies the milk producer has followed all safety and quality standards laid out by the FDA in the “Grade ‘A’ Pasteurized Milk Ordinance (PMO)”. This document specifies proper pasteurization and microbial testing requirements for milk samples, but also prescribes standards for farm equipment, water supply and animal drug residue limits. Compliance with all standards is strictly overseen by individual state health departments via regular inspections of dairy farms, transport tankers, and processing plants. Some retail distributors require even higher standards than what are mandatory for Grade A classification, making “Grade A” the minimum standard quality for fluid milk.

Grade A milk is classified into three classes (I, II, III) each commanding a separate price for suppliers. The premium class, Class I, receives the highest quality marks in terms of smell, color, and taste and is suitable for drinking and adding to cereal and fetches the highest price. Each subsequent class scores slightly lower on sensory tests and may be sent off to be made into cheese or ice cream.

Grade B

Grade B milk is from facilities that do not meet one or more of the quality standards required for Grade A certification, but may be used in milk products such as cheese and butter if it passes Grade B standards. Grade A milk sells for a higher price than Grade B and much of the market for Grade B milk has disappeared. Only about 2% of the milk supply for milk products comes from Grade B milk (3).

Raw Milk

Raw milk (unpasteurized) is not generally available to the public because of the health risks it imposes, and there are no uniform standards producers must adhere to. Depending on individual state regulations, raw milk may be available for purchase at retail establishments, as part of a contractual herd share agreement, direct to consumer sales from the farmer, or the sale may be completely banned. In Colorado, raw milk may not be sold at any retail establishment but is allowed to be given in exchange for payment for a cow’s boarding and feeding (herd share agreement). In other states, like California, raw milk may be sold to consumers if the raw milk producer holds a special permit and adheres to specific sanitation requirements and places a health warning label on the container.

In spring of 2024, bipartisan legislation was brought to committee in the Colorado senate proposing a relaxation of raw milk sales (4). If passed, the bill would have allowed for the direct sale of raw milk from farm to consumers if the producer is registered with the department of health, uses sterile containers, places a health warning label on containers, transports the milk at or below 40 degrees F and protected from sunlight, and sold within 5 days of filling the container. The producers may not sell raw milk at any retail food establishment, nor can they publish any statement that implies the department of health approves or endorses the sale of their product. The bill failed in committee and did not make it to the floor for a full senate vote.

Foodborne Outbreaks and Recalls

Before pasteurization was a required practice for milk producers, nearly one quarter of all foodborne and water contamination illnesses were due to the consumption of milk (as reported in 1938) (5). This was in part because as urbanization increased, the demand for milk prompted a milk transportation system that lacked proper refrigeration leading to bacterial overgrowth during delivery. After pasteurization became common practice, milk safety significantly increased, with reported outbreaks making up less than one percent of all outbreaks per year (6). The CDC defines “outbreaks” as “two or more persons experience a similar illness resulting from the ingestion of a common food”.

Pathogens of concern

- Salmonella: This bacterium is common among dairy cows. A 2007 USDA report showed that 40% of surveyed dairies had positive fecal cultures for salmonella in at least one cow (7). Salmonella can contaminate milk via fecal matter or may be shed directly in milk. A 1998 report using data from the USDA showed that the prevalence of Salmonella increases as dairy herd size increases. Fifty- six percent of dairies with 400 cows or more had at least one cow carrying Salmonella, whereas only about five percent of dairy herds of less than 100 cows had at least one infected cow (8).

- One particular subtype of Salmonella, Salmonella Dublin, is the most common strain found in US dairy herds and is infectious to humans. It is particularly worrisome given its association with severe disease and multi-drug resistance (9).

- Escherichia coli: Contamination occurs from environmental sources as well as mastitis infection. Infection with certain subtypes of E. coli is very serious for vulnerable adults and children, causing gastrointestinal infection and potentially kidney failure.

- Listeria: Listeria monocytogenes and other species of Listeria are particularly dangerous for pregnant women because they can infect the placenta and fetus, leading to abortion, stillbirth, or severe neonatal infection.

- Mycobacterium bovis: M. bovis can cause tuberculosis in humans, affecting multiple organs, including the lung, lymph nodes, and central nervous system. Dairy cows can be infected by other cows that were not adequately screened for disease, or by infected farmworkers. Diligent testing of cows, as required by law, and culling of infected cows has nearly eliminated all human cases in the US of tuberculosis originating from milk. Cases continue to occur in countries where pasteurization is not a standard practice (10).

- Brucella abortus: This bacterium causes significant damage to dairy herds because it can cause abortions and stillbirths. It is also capable of infecting humans and causes severe joint and muscle pain as well as recurring fever. Because of the industry economic impact of this pathogen, there are strict testing requirements for Brucella abortus. Vaccination of female cattle may also be a requirement depending on state regulations (11).

- Campylobacter jejuni: This bacterium can adulterate the milk supply through contamination of milking equipment from fecal particles or dirty udders. Campylobacter spp. cause the most bacterial diarrheal illnesses in the US, but are usually only serious in the elderly or children younger than five (12).

- Cryptosporidium: A parasite found in contaminated water and spread through fecal particles from cows. It can cause watery diarrhea in humans (13).

- H5N1 Avian Flu: In late March 2024, highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAI) of the H5N1 subtype was detected for the first time in nasal swabs and milk of dairy cows, increasing concern that HPAI A (H5N1) viruses may enter the human food chain. In April of 2024, unpasteurized milk samples in herds of dairy cows across several states tested positive for the virus H5N1, and as of July 2024, Colorado had reported the highest numbers of infected cows in the country (14)

Research from the University of Wisconsin and Texas A&M (2024) indicated that under laboratory conditions, HPAI A(H5N1) virus in untreated milk could infect susceptible animals that consume it. The authors posited that HPAI H5–positive milk poses a risk when consumed untreated, but heat inactivation under the laboratory conditions used reduced HPAI H5 virus titers by more than 4.5 log units (50,000-fold reduction). The authors stressed that bench-top experiments do not recapitulate commercial pasteurization processes (15). All milk produced from symptomatic cows is being disposed of and not entering the milk supply as of this writing (16).

Milk Outbreaks

According to the CDC national outbreak reporting system (NORS), in the thirty years between 1991 and 2021, milk has been attributed to 297 outbreaks, 6,126 illnesses, 347 hospitalizations, and 7 deaths. Because milk can be classified into two categories that present very different risk profiles, both raw and pasteurized outbreaks will be discussed.

Pasteurized Milk Outbreaks

- 2007 Massachusetts Listeria outbreak: Five cases of listeriosis were traced back to a family owned farm with an onsite pasteurization facility. Three deaths occurred, including one 37 week stillbirth. All implicated milk products were pasteurized. All pasteurization equipment and processes were up to date and adequate as far as temperature and flow regulations, however, environmental swabs from the processing facility showed Listeria contamination, especially near floor drains and hoses used for cleaning equipment. The facility did not have an environmental monitoring system for Listeria, which is not required by law (17).

- 1987 Salmonella outbreak: The largest outbreak of milk-born salmonellosis in history in the United States. Over 16,000 culture-confirmed cases and an estimated 160,000 persons sickened by contaminated milk from a single dairy operation. The contamination was speculated to happen after pasteurization in the facility with unsanitary conditions (18).

Raw Milk Outbreaks

- 2024 California; Salmonella outbreak: At least 171 cases of salmonellosis were connected to raw milk from a Fresno dairy, making it the largest outbreak from raw milk in the last decade (19,20).

- 2023 Minnesota; Cryptosporidium outbreak. Eight people were sickened, one was hospitalized after consuming raw milk from the Healthy Harvest Farm (21).

- 2017-2019; Brucella abortus RB51. Three confirmed cases of human brucellosis traced back to raw milk consumption from Texas and Pennsylvania dairies (22). These cases were due to the shedding of bacteria that comes from a vaccine given as standard of care to all dairy cows.

- 2016 Colorado; Campylobacter jejuni outbreak. Twelve confirmed and 5 suspected cases of campylobacteriosis. Infections were traced back to raw milk consumption from a herd share dairy. This outbreak was particularly concerning because 5 isolates present in samples from the outbreak were antibiotic resistant (23). One hospitalization occurred, but there were thankfully no deaths.

Comparing Raw Milk Outbreaks with Pasteurized Milk Outbreaks

The IFSAC (Interagency Food Safety Analytics Collaboration) is a collaborative entity among FDA, USDA, and CDC that monitors foodborne illness outbreaks and develops reports identifying sources of outbreaks. The reports also determine the degree to which categories of foods contribute to the outbreak illnesses. The most accurate methods for reporting were developed in 2017, making the last 6 years’ reports the most reliable sources for sources of foodborne illnesses each year. The reports focus primarily on 3 pathogens: E. coli, Listeria, and Salmonella. Campylobacter outbreaks are also considered, but since most Campylobacter infections are sporadic and do not occur as outbreaks, they are not usually included with the reports. However, historically, foods that are associated with Campylobacter outbreaks as defined by IFSAC, include raw milk and chicken livers. Seventeen food categories (i.e., chicken, fruits, eggs, dairy etc.) are assigned a percentage representing their contribution to each of the three major food borne pathogens (E. coli, Listeria, and Salmonella). A recent IFSAC report (1998-2021) shows dairy most significantly contributes to the Listeria category (37.4% of cases due to dairy) (24). Unfortunately, the “dairy” category does not differentiate between outbreaks due to raw milk and pasteurized milk. However, FDOSS (foodborne disease outbreak surveillance system) reports breakdown the number of outbreaks between pasteurized, raw, and unknown milk, although they do not report how many illnesses are associated with each outbreak. This makes it difficult to quantify the actual risk of raw milk consumption.

One publication from coauthors at CDC (25) made a direct comparison between the risk of milk-borne illness from raw versus pasteurized milk. The authors calculated the number of outbreaks per total pound of consumed milk, which resulted in a 150 times higher rate of illness from raw milk compared to pasteurized milk. The authors used CDC case numbers of milk-borne illnesses attributed to either raw or pasteurized milk between 1993-2006 and estimated the percentage of consumed raw and pasteurized milk based on the 2005-2006 national diet survey results (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey). Total milk production reports for the US were used to tally a 14 year grand total of milk consumed by the public (note that it was not stated how much of the yearly milk production is actually consumed as fluid milk, as opposed to made into other processed dairy products). Using the percentages obtained from NHANES, a total number of pounds were estimated to be consumed in the 14 year period for both raw and pasteurized milk.

Production

Milking process

In modern dairy farms, automated milking machines attached to cow udders use vacuum suction to extract milk from each teat. Teats must be disinfected and stimulated before milk is withdrawn. Large operations use milking machines which spray disinfectant to automatically clean teats after which a pulsating vacuum is attached to collect milk. Less automated systems may require the human milker to wash and stimulate teats before attaching the suction tubes of the milk machine to the udder. Each vacuum tube connected to a teat has a metal or plastic outer material with a flexible inner membrane that pulsates as vacuum is applied and released. Sensors in the teat cups automatically release the teat when flow decreases below a set threshold.

As milk leaves the cow teat, it runs through “milk hoses” to a main pipeline that directs the collected milk into a chamber for cooling. Milk must be cooled and maintained at 4℃ within 2 hours of milking.

The majority of milk processing takes place off-site from the dairy farm, requiring raw milk to be collected from farm holding tanks into refrigerated tanker trucks for transport to processing facilities where it is collected in large refrigerated silos. Depending on the operation, samples may be collected from the dairy farm tanks for quality and pathogen testing before transport to the processing facility. This practice helps prevent contaminated dairy milk from entering the larger scale bulk tanks that collect from multiple dairies. Additional testing may be performed from samples pulled from tanker trucks that have combined multiple dairy milk harvests. After arrival at the processing facility, and if the milk passes all quality tests, the milk enters large silos awaiting processing and pasteurization.

Pre-Pasteurization Processing

Milk goes through a series of processing procedures before it is pasteurized in order to maximize pasteurization effectiveness. For instance, impurities or sediments in raw milk may contribute to uneven heating or may clog or damage processing equipment, therefore clarification or filtration must occur before raw milk is heated during pasteurization. Impurities include flies, hair, straw, or other foreign matter.

Pasteurization

Raw milk is considered a health hazard because of the potential risk of microbial contamination originating from infections, manure particles, milking machinery, pasture or holding pens, animal feed, or farm water. Listeria, E. coli, Salmonella, and Campylobacter, are some of the more common and serious contaminants found in some sources of raw milk. Less common, but important pathogens include Brucella abortus and Mycobacterium bovis. Pasteurization kills these pathogens with heat and is required by the FDA for the sale of milk for human consumption.

Typical pasteurization protocols are as follows:

- HTST (High Temperature Short Time) pasteurization is widely used and requires milk to reach a temperature of 161℉ for 15 seconds.

- HHST (High Heat Shorter Time) pasteurization heats milk to 191℉ for 1 second.

- UP (Ultra Pasteurized) is milk heated to 280℉ for 2 seconds.

Microbial Testing for Quality Control

Microbiological testing is required for Grade “A” milk. These tests include:

- Total Bacterial Counts (TBC): Measures total load of bacteria in a milk sample, but does not differentiate which types of bacteria predominate the sample. TBC is expressed in colony-forming units per milliliter (cfu/ml) and high numbers indicate possible sanitation delinquencies. Raw milk meant for pasteurization can have up to 100,000 cfu/ml from a single dairy operation, or up to 300,000 cfu/ml for a bulk tank batch containing multiple sources of milk.

- Somatic cell counts: Measures white blood cells and epithelial cells from the cow udder tissue. High counts indicate possible mammary infection (mastitis).

- Coliform counts: Indicator of fecal contamination*. Microbial cell densities of >100 cfu/ml are considered poor quality and may be the result of improper cleaning of the teat before attachment of the milking apparatus.

- *Prior to better classification of coliform bacterial categories, it was believed coliforms were primarily from fecal contamination and did not survive well outside the digestive tract of mammals. More recent research revealed coliforms can also be environmental contaminants and may not be the best indicator for fecal contamination but could be a result of dropped milking units, farm water/produce contamination, or substandard cleaning of farm equipment (26).

Preliminary Incubation (PI) count: This is primarily an assessment of milking equipment sanitation. Bacteria counted in this procedure are those that can grow in cold environments. While these bacteria do not survive pasteurization, they do produce enzymes that survive and will impact milk quality, even when milk is appropriately chilled.

Contamination points

Originating from the cow:

- Mastitis Infections, and some systemic infections whereby bacteria may be shed in milk

- Soiled teat or udders from bedding, ground, or exposure to leg infections.

- Teat Cleaning: Automatic teat cleaning needs to be correctly calibrated to remove sufficient amounts of disinfectant before suction occurs. Udder cleaning towels must be properly stored and not shared between animals.

- Manure particles present on teats/udders.

- Manure contains enteric organisms harmful to human health and is a common contaminant in milking parlors and holding pens.

- Contaminated animal feed may be a source of E. coli and Listeria and may be shed in feces (to subsequently contaminate milk in manure) or act as an environmental contaminant.

Originating from milking machinery:

- Machine milking may increase risk of bacterial entry into the teat, therefore hygienic maintenance of machine parts must be a sustained effort (6).

- Teat Cup liners: These are routinely cleaned and rinsed between milkings (morning and evening), however, typically not between each cow at one milking.

- Milk lines bringing milk to the storage tank must be flushed and sanitized, as does the storage tank itself between milkings.

- Other machinery: Not all components of the milk machine will be in contact with the milk but should still be wiped clean and kept in clean order. This would include the vacuum and pulsation systems, outside of hoses, and the milking parlor floor.

- Temperature Abuse:

- Improper cooling. Milk must be cooled to 40℉ or less within 2 hours of milking the cow to prevent rapid growth of harmful bacteria.

Originating from a milking and/or processing facility (27):

- Improperly cleaned tanker trucks. Truck tanks must be sanitized each day after batch transport, or in between multiple deliveries in one day (28).

- Water: Water used to rinse udders, flush hoses, clean parlors, etc. should be potable and inaccessible to rodents and insects.

- Post pasteurization contamination can result from:

- Biofilm adhesions to inside of distribution pipes

- Unsterilized milk containers

- Unhygienic practices of production workers

- Improper holding temperatures of finished milk product during transportation, in-store holding, and consumer households (29).

Raw Milk

Raw milk is subject to all of the contamination points listed above. As milk leaves the udder, it is generally free from harmful pathogens, however, the cleanliness of the environment and equipment matters greatly to how safe raw milk is before consumption (30). Pathogenic bacteria can easily enter the teat canal from straw/animal bedding, as a cow lays on the ground, from feces, and even milking equipment. Even with proper cooling techniques and use of sterile canisters there remains risk of contamination from fomites present in the milking parlor and from farm and transportation workers.

Food Safety

Milk is especially hospitable to microbial growth because of its nutrition profile and liquid state. The sugars and nutrients in liquid milk are highly bioavailable and microorganisms are able to proliferate throughout the highly penetrable matrix (as opposed to a solid food).

In the 19th century, prior to the acceptance of pasteurization of milk, it had been noted that formaldehyde was added to milk to prevent “souring”. Other procedures to improve shelf life involved thinning of milk by adding water, chalk dust and/or small amounts of gelatin (31). The federal Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 banned the use of formaldehyde from the food supply which includes milk pasteurization of milk did not become fully adopted by the medical and public health community until the 1930’s (32).

In Colorado, CDPHE monitors milk and milk products produced in Colorado and regulations are based on the federal Grade “A” Pasteurized Milk Ordinance. CDPHE regularly performs inspections and sample products at all dairy farms, dairy plants and milk plants as well as checks milk and dairy plant pasteurizers and pasteurization procedures (33). Other states may have different requirements and oversight mechanisms.

Pasteurized Milk Safety

Pasteurization eliminates the majority of microbial pathogens present in milk after the milking process has occurred, however milk remains vulnerable to environmental contaminants and conditions as soon as it leaves the heating chambers. After pasteurization, there is still a chance of microbial contamination and spoilage if proper food safety precautions are not taken.

Post pasteurization contamination (PPC) is a frequent occurrence and has been noted to be found in nearly 50% of pasteurized milk samples (34). The majority of pathogens do not survive pasteurization, and those that do are typically unable to replicate at refrigerator temperatures (approx. 3° C). However, some species, like Pseudomonas spp. are relatively cold-tolerant and can proliferate even at refrigerator temperatures.

Post Pasteurization Microbes

- Pseudomonas spp.: primary source of PPC contamination. They are not heat resistant, therefore their presence in milk samples indicate a post-pasteurization corruption.

- Coliforms: gram-negative, lactose-fermenting rod bacteria that are facultatively anaerobic (able to survive with and without oxygen). They contribute to the “souring” of milk. Coliforms are easily destroyed during pasteurization, therefore their presence indicates PPC. This is problematic because some coliforms are psychrotolerant (cold-tolerant) and can proliferate at a steady rate for over 10 days, leading to a substantial decrease in milk sensory properties and therefore shelf-life.

- Non-Pseudomonas, non-coliform gram-negative bacteria, such as Aeromonas spp.

- Gram-positive spore-forming bacteria, such as Bacillus cereus.

Raw Milk Safety

Raw (unpasteurized) milk poses more of a disease risk to humans than pasteurized milk because it is subject to all sources of contamination during the milking process plus the post milking susceptibilities for contamination (transport, storage, packaging). Between 2000 and 2019, a meta-analysis of 20 studies identified that disease-causing bacteria were present, on average, in 3.6 to 6 percent of raw milk sampled from on-farm bulk tanks (35). According to a study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration, there were 202 disease outbreaks in the US due to drinking raw milk between 1998 and 2018, leading to 2,645 illnesses, 228 hospitalizations, and three deaths (36). Some raw milk producers will perform microbial testing on their milk, but there are no standards to which all producers adhere and there are major limitations in the testing itself.

Limitations of raw milk testing

Ensuring the safety of raw milk is difficult, even when testing for microbial contamination is employed. Several issues surround the practice of using product testing as an indication of safety (6). These include:

- Sampling strategies may not be comprehensive enough to detect pathogens because contamination can occur sporadically, and it is difficult to determine an adequate frequency of testing that balances cost and sufficiency.

- Total bacteria counts and somatic cell counts do not directly correlate to pathogenic contamination. Low bacterial counts can still include pathogenic species.

- Pathogens are not evenly distributed throughout a milk sample, as some pathogens have been found to associate with the fat portion.

- Even if a pathogen count is very small at the time of testing, it may grow to a dangerous level at some point after testing, especially if there is a break in the cold chain.

- It is impossible to test for every possible pathogenic contaminant.

Consumption

For adults, the USDA recommends 3 cups of milk per day, or an equivalent amount in dairy products. As of 2022, adults are consuming only around ⅔ of a cup per day, which is 47% less than they were drinking in 1975. Despite this precipitous drop in fluid milk consumption, milk production continues to increase in the US with a 96% increase since 1975. This escalation in production meets consumer demand for yogurt and cheese, which has increased dramatically over the past five decades. Researchers investigating the dwindling consumption rates have identified factors like decreased cereal consumption and increased consumption of alternative beverages as possible drivers. However, the decline is greater than can be explained by increased competition with sugar sweetened beverages like sports drinks, soda, and teas. Plant based milks have cut into the dairy market, though the increase in plant based milks is not enough to account for all of the decline in cow’s milk consumption (37).

Nutrition

Milk is inherently nutritious as it is the natural first food for mammalian infants, providing a complete source of essential nutrients necessary for growth and development. It contains a perfect balance of proteins, fats, vitamins, and minerals tailored to support the early stages of life. Milk is one of the few whole foods that contain substantial amounts of all three macronutrients. Each cup of cow’s milk contains:

- 12 g of carbohydrates, most of which comes from “milk sugar”, or lactose. This disaccharide is a combination of glucose and galactose and requires a specific enzyme, lactase, for its metabolism. Many people stop producing this enzyme as they age and therefore become lactose intolerant because they cannot break down the milk sugars. These undigested sugars

- 2 g of protein. Milk proteins are complete proteins meaning they are comprised of all essential amino acids. Like other animal proteins, milk proteins are well suited to meet human requirements because they contain amino acids in similar ratios to those found in human proteins.

- 8 g of fat (whole milk). Fat content is variable depending on the type of milk processing that is desired (whole,2%, skim), as well as the cow’s diet and breed.

While there have been questions raised regarding the nutritional relevance of milk in the adult diet, there is no denying milk can serve as a good source of micronutrients and is a relatively unprocessed beverage choice. Water makes up 87% of milk, making it a hydrating drink that also contains many minerals and vitamins. Calcium is highly bioavailable in the form it takes in milk, calcium-phosphate. The proteins in milk (casein and whey) as well as the sugar (lactose) increase the solubility of calcium, allowing our bodies to absorb it efficiently. Milk naturally contains vitamin B12, vitamin B2 (riboflavin), and vitamin A. Fortified milk contains vitamin D.

Raw milk is growing in popularity due to several perceived benefits and a shift towards natural and traditional food practices. Proponents of raw milk** cite epidemiological evidence showing a protective effect from allergic conditions like eczema, rhinitis, and asthma in children who consume raw milk. Three large studies, the GABRIEL (10,000 children) and the PARSIFAL (15,000 children), and the PASTURE (1133 children) analyzed different components of the “Farm Effect”, known as the phenomenon where children growing up on, or near, a farm have lower risk of atopy and related conditions. All studies collected data demonstrating raw milk was independently associated with reduced rates of asthma, atopy, and hay fever in children (38–42).

The FDA asserts pasteurization “Does NOT reduce milk’s nutritional value”, although some studies have shown there are differences in vitamin content between raw and pasteurized milk samples (36). One meta-analysis of 40 studies measuring vitamin differences between raw and pasteurized milk found significant reductions in vitamins B2, B12, E, C, and folate after pasteurization, and an increase in Vitamin A (43). Because a well-rounded diet provides much larger quantities of these vitamins than milk alone, the decrease in vitamin content is considered negligible. Whether raw milk is nutritionally more desirable than pasteurized milk cannot be definitively addressed when considering only macro and micro nutrients. Bioactive peptides, immunoglobulins, fatty acids, bacteria, and enzymes are all components of raw milk that may have beneficial impacts on human health but have not yet been sufficiently studied in the literature. Importantly: regardless of raw milk’s potential for supporting human health, it carries a significant health risk that arguably outweighs any benefits for most consumers.

** An important distinction is made by raw milk proponents between raw milk intended for pasteurization, and raw milk intended for consumption. They suggest consuming raw milk only from dairies adhering to more stringent hygienic standards than dairies producing milk destined for pasteurization. The Raw Milk Institute (RAWMI), a private organization, developed “Common Standards” in 2012 (updated in 2020) for raw milk diaries to follow in order to reduce the risk of milk contamination, although there is no regulated oversight by a government agency.

References

Bibliography

- Bleasdale M, Richter KK, Janzen A, Brown S, Scott A, Zech J, et al. Ancient proteins provide evidence of dairy consumption in eastern Africa. Nat Commun. 2021 Jan 27;12(1):632.

- Early History · The American Dairy Industry · [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 8]. Available from: https://www.nal.usda.gov/exhibits/speccoll/exhibits/show/the-american-dairy-industry/early-history

- Blayney DP. The Changing Landscape of U.S. Milk Production [Internet]. USDA; 2002 Jun.

- Authorizing Direct-to-Consumer Sales of Raw Milk | Colorado General Assembly [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 8]. Available from: https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/sb24-043

- Alegbeleye OO, Guimarães JT, Cruz AG, Sant’Ana AS. Hazards of a ‘healthy’ trend? An appraisal of the risks of raw milk consumption and the potential of novel treatment technologies to serve as alternatives to pasteurization. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2018 Dec;82:148–66.

- Holschbach CL, Peek SF. Salmonella in dairy cattle. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2018 Mar;34(1):133–54.

- www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/dairy96_is_ecoli_salm.pdf

- Velasquez-Munoz A, Castro-Vargas R, Cullens-Nobis FM, Mani R, Abuelo A. Review: Salmonella Dublin in dairy cattle. Front Vet Sci. 2023;10:1331767.

- Epidemiologic Notes and Reports Bovine Tuberculosis — Pennsylvania [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 26]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00001581.htm

- Daniels J. Interview with Colorado State University Professor. 2024.

- Campylobacter [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 26]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/campylobacter

- Symptoms of Crypto | Cryptosporidium (“Crypto”) | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 5]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/cryptosporidium/signs-symptoms/index.html

- HPAI Confirmed Cases in Livestock | Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 18]. Available from: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-detections/hpai-confirmed-cases-livestock

- Guan L, Eisfeld AJ, Pattinson D, Gu C, Biswas A, Maemura T, et al. Cow’s Milk Containing Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus – Heat Inactivation and Infectivity in Mice. N Engl J Med. 2024 Jul 4;391(1):87–90.

- Questions and Answers Regarding Milk Safety During Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) Outbreaks | FDA [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 2].

- Outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes Infections Associated with Pasteurized Milk from a Local Dairy — Massachusetts, 2007 [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 3]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5740a1.htm

- Ryan CA, Nickels MK, Hargrett-Bean NT, Potter ME, Endo T, Mayer L, et al. Massive outbreak of antimicrobial-resistant salmonellosis traced to pasteurized milk. JAMA. 1987 Dec 11;258(22):3269–74.

- Dozens were sickened with salmonella after drinking raw milk from a California farm [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 26]. Available from: https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/dozens-sickened-salmonella-drinking-raw-milk-california-farm-rcna161422

- Raw Milk Is Booming. A Salmonella Outbreak Highlights Its Risks. – The New York Times [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 5]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/07/19/well/raw-milk-health-salmonella.html

- Health officials investigating outbreak linked to raw milk – MN Dept. of Health [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 7]. Available from: https://www.health.state.mn.us/news/pressrel/2023/milk090123.html

- Gruber JF, Newman A, Egan C, Campbell C, Garafalo K, Wolfgang DR, et al. Notes from the Field: Brucella abortus RB51 Infections Associated with Consumption of Raw Milk from Pennsylvania – 2017 and 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Apr 17;69(15):482–3.

- Burakoff A, Brown K, Knutsen J, Hopewell C, Rowe S, Bennett C, et al. Outbreak of Fluoroquinolone-Resistant Campylobacter jejuni Infections Associated with Raw Milk Consumption from a Herdshare Dairy – Colorado, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018 Feb 9;67(5):146–8.

- The Interagency Food Safety Analytics Collaboration (IFSAC).

- Langer AJ, Ayers T, Grass J, Lynch M, Angulo FJ, Mahon BE. Nonpasteurized dairy products, disease outbreaks, and state laws-United States, 1993-2006. Emerging Infect Dis. 2012 Mar;18(3):385–91.

- Martin NH, Trmčić A, Hsieh T-H, Boor KJ, Wiedmann M. The evolving role of coliforms as indicators of unhygienic processing conditions in dairy foods. Front Microbiol. 2016 Sep 30;7:1549.

- Reinemann DJ. Milking machines and milking parlors. Handbook of farm, dairy and food machinery engineering. Elsevier; 2019. p. 225–43.

- COLLECTION AND RECEPTION OF MILK | Dairy Processing Handbook [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 13]. Available from: https://dairyprocessinghandbook.tetrapak.com/chapter/collection-and-reception-milk

- A response to the request from The Maryland House of Delegates’ Health and Government Operations Committee December 8, 2014.

- Martin NH, Evanowski RL, Wiedmann M. Invited review: Redefining raw milk quality-Evaluation of raw milk microbiological parameters to ensure high-quality processed dairy products. J Dairy Sci. 2023 Mar;106(3):1502–17.

- Part I: The 1906 Food and Drugs Act and Its Enforcement | FDA [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 17]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/changes-science-law-and-regulatory-authorities/part-i-1906-food-and-drugs-act-and-its-enforcement

- Blum. The Poison Squad. Penguin; 2018.

- About the Milk Program | Department of Public Health & Environment [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 17]. Available from: https://cdphe.colorado.gov/milk-program/about-the-milk-program

- Martin NH, Boor KJ, Wiedmann M. Symposium review: Effect of post-pasteurization contamination on fluid milk quality. J Dairy Sci. 2018 Jan;101(1):861–70.

- Williams EN, Van Doren JM, Leonard CL, Datta AR. Prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella spp., Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, and Campylobacter spp. in raw milk in the United States between 2000 and 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Food Prot. 2023 Feb;86(2):100014.

- The Dangers of Raw Milk: Unpasteurized Milk Can Pose a Serious Health Risk | FDA [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 1]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/food/buy-store-serve-safe-food/dangers-raw-milk-unpasteurized-milk-can-pose-serious-health-risk

- Stewart H, Kuchler F, Dong D, Cessna J, Stewart H, Kuchler F, et al. Examining the Decline in U.S. Per Capita Consumption of Fluid Cow’s Milk, 2003–18. UNKNOWN. 2021;

- Waser M, Michels KB, Bieli C, Flöistrup H, Pershagen G, von Mutius E, et al. Inverse association of farm milk consumption with asthma and allergy in rural and suburban populations across Europe. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007 May;37(5):661–70.

- Loss G, Apprich S, Waser M, Kneifel W, Genuneit J, Büchele G, et al. The protective effect of farm milk consumption on childhood asthma and atopy: the GABRIELA study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Oct;128(4):766-773.e4.

- Perkin MR, Strachan DP. Which aspects of the farming lifestyle explain the inverse association with childhood allergy? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006 Jun;117(6):1374–81.

- Müller-Rompa SEK, Markevych I, Hose AJ, Loss G, Wouters IM, Genuneit J, et al. An approach to the asthma-protective farm effect by geocoding: Good farms and better farms. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2018 May;29(3):275–82.

- Whitehead J, Lake B. Recent trends in unpasteurized fluid milk outbreaks, legalization, and consumption in the united states. PLoS Curr Influenza. 2018 Sep 13;10.

- Macdonald LE, Brett J, Kelton D, Majowicz SE, Snedeker K, Sargeant JM. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of pasteurization on milk vitamins, and evidence for raw milk consumption and other health-related outcomes. J Food Prot. 2011 Nov;74(11):1814–32.