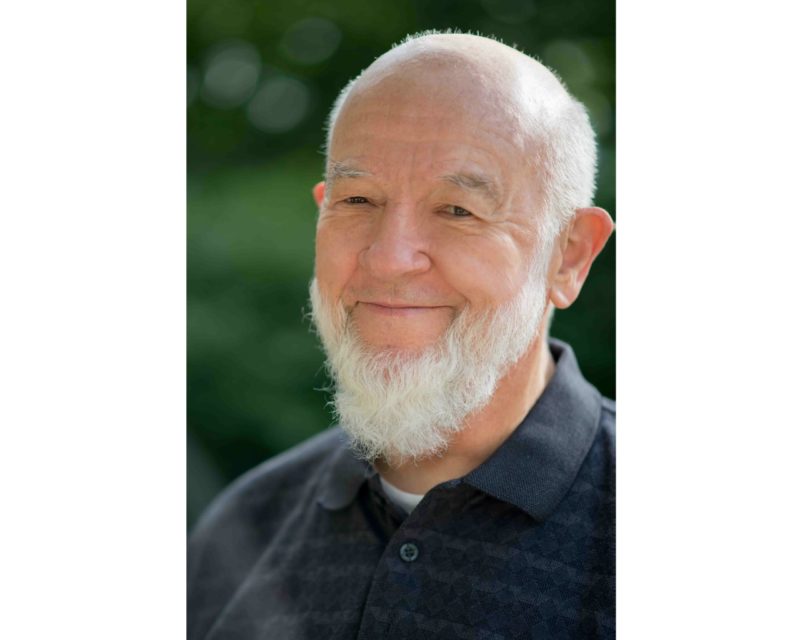

Bruce's Biography

CSU Service 1973 to 2008

Faculty, School of Social Work

Personal Background

Almost sixty years ago, a wise friend, Dr. Jay MacCreary, sat with me on the sundeck of his beautiful home overlooking the vast Los Angeles basin, and asked a provocative question: “Bruce, do you know why I took you to Mexico with my family?” I sensed that he was not seeking thanks. I responded clumsily, “Ah-h, no not really.” He looked at me squarely and said, “A fool sent to Rome is better than a fool kept at home.” That perceptive observation has stayed with me all these years.

The adage came to mind, again, when Victoria Keller asked me to reflect on becoming a social worker for inclusion in the Legacies Project.

Family and Early History

I was born in 1937 in the Good Samaritan Hospital of Los Angeles. I am the second son of an economist and an attorney. I have an older brother, Jack, and two younger sisters, Mary Anne and Carol. Like many middle class families of that era, we were each born five years apart. We were raised in a solidly Protestant, Victorian household.

My early memories are of the joys of a stimulating family and neighborhood life especially food – the buttery sweetness of the Schindler’s cookies made from recipes brought when they fled the Holocaust, the savor of chili dogs at Tail o’ the Pup, eating Sardines with my Dad, and Sunday dinners with the family. Los Angeles is in my head. The cultures of one of the world’s great cities move me along with corresponding racism and classism that never made sense.

The first big event that I remember is the bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Dad had been in the ROTC throughout high school, and college, and commissioned in the Army after graduation. His unit was immediately called to war. Within a month, our family moved to Muskogee, Oklahoma to spend “his last days” with him before his unit was deployed to India. Muskogee’s major industry was Fort Sill preparing troops for battle. The Field Artillery was our family business, and “Caissons go rolling along” our anthem. Telephones were answered with the rank and last name of the resident officer. Life is about good order.

It was in Muskogee that I first experienced real cold and snow. I also discovered people called

“hobos” living outdoors. They camped at the end of our street, across the railroad tracks. At night I watched their fires burning against the bitter cold. One afternoon, there was a disturbance. The police were raiding the hobo camp. My brother, Jack, and I rushed to the edge of my known world to see the excitement. When we got there the Paddy Wagons were pulling away. Everyone was gone. We crossed the train tracks and played with the camp fires. We discovered that the hobos had roasted potatoes in the hot ashes. We ate potatoes fresh baked. They were wonderful. I discovered that life holds many wonders across the tracks.

The winter of 1942 pressed hard on Muskogee. We were house bound for weeks. When the snow and cold let up, I rushed out to play. There was a beautiful frozen pond. The ice was sparkling and crisp, and lightly dusted with flakes. I cautiously walked onto the pond, careful not to lose my balance. The ice broke. I sank into the icy water. There followed a great commotion of alarmed adults. And I learned another lesson: It is alright to go out on the ice, if you are willing to accept the consequences.

The war reshaped our family. Mom was overwhelmed with Dad’s business, three young children including a newborn, Mary Anne, and there were unanticipated challenges. Six months after Dad’s command was sent to Asia, my brother was sent to boarding school. I was diagnosed with a “virus” involving chronic bleeding from my nose and lungs, and difficulty sleeping. After a lot of unsuccessful doctoring, the recommendation was to send me away. The chosen site was a desolate cabin in the Mojave Desert. My caretaker was a loving city gal who believed that gin would sustain her through the heat, sand, wind, and isolation of desert life.

,

In some ways we were all in the war. I had it pretty good as a “desert rat.” My symptoms gradually cleared up. Animal life was everywhere and fascinating. I could walk the short cut across the desert to school. The Mojave taught me that, like the snakes, horned toads, and jackrabbits, life is doing what has to be done; people do the best they can; and walking through the desert is beautiful if you pay attention.

World War II ended and the Hall Family was back together. During the birth of Carol, the youngest sister, Mom had a heart attack. I was concerned but confident – no one I knew had ever died. Mom “just needed a little rest.” A lot of attention was given to the new baby. We all took turns caring for her.

The house we rented was by a harbor. As the oldest, Jack and I had chores to do in addition to school work. Otherwise, we were free to roam. Dad had long days driving a hundred miles into Los Angeles to rebuild his practice. The house came with a rowboat, and Jack and I took to it. The ocean was a beautiful and lively environment, like the desert. We swam off the dock with halibut, bass, small sharks, and stingrays.

The harbor school bus was a great meeting place, and soon a small group of boys formed. We cruised the surrounding waters in the rowboat, and staged “commando landings” on docks and vacant properties.

It was Charlie Murray or Bill Ring who said, “We’re just like the Blackhawks!” That observation struck a spark. Like the Blackhawk Squadron of comic book fame, we operated from “a hidden island fighting evil and oppression.” Blackhawk comics became a guide. We made Blackhawk insignia from yellow felt, and sewed them on our shirts. We shouted the motto: “Over land, over sea, we fight to make men free!” and patrolled the beaches and boardwalks. The Blackhawks bonded with Sheriff Bill, the local law officer. He encouraged us to “watch for strangers and speeders.” We kept him informed of cat drownings, unlocked houses, and loud, drunken parties.

With the Blackhawks I learned the power of groups to create culture, and help people sustain one another.

Forty-seven was a very good year. Mom had fully recovered. She was the hub of our family’s life. Little sister, Carol, blossomed into an energetic and playful toddler. Mary Anne was dresses, frills, and patent leather shoes. Dad’s practice had flourished. We had returned to Los Angeles and moved into an active, ethnically diverse neighborhood of families and kids. The action was in the streets. I loved it. Girls and boys prowled 60 square blocks and more. Games of “Hide and Go Seek” and “Capture the Flag” would span an entire block, when we were not at school.

First Job

The gods of commerce determined that I was big enough to work. It was easy to get a job. My classmates introduced me to a route manager, and I soon was delivering the Los Angeles Times – door-to-door, fifty papers, 3 to 5 a.m. every morning, on Norton Ave. from Olympic to Pico. It was demanding work, especially on New Year’s Day when each paper weighed several pounds. Going into multiple, darkened apartment buildings where everyone was asleep, except adults who loved the night and hated kids, was the real justification for the high rate-of-pay – one cent per paper per day, $3.50 a week.

In this neighborhood, I found my first “sweetheart.” She was a dark-haired beauty – a tall, graceful, fifteen-year-old – who was reported to be attracted to me though I was a head shorter, and several years younger. She said there was only one thing I had to do to prove my love: beat-up her brother, Steve, who was the acknowledged, feisty, foul-mouthed, community troublemaker.

My friends said that to bind our relationship I also would have to buy her something personal. I selected a gold plated bracelet with a big, gold heart on it. The cost of engraving, alone, was equal to the price of the bracelet, but where the heart is concerned no cost is too great. On one side was her name, “Julie” and on the other, mine.

The fight with Steve was an anti-climax. The gathering was the event. Thirty or more kids and adults stood on their porches and in little groups around the field of combat, a neighbor’s front lawn. Brother Steve didn’t bring the rage of his sibling rivalry to the fight. He lost, to the loud cheers of the onlookers.

Perhaps Steve knew his sister better than I did. A month later, it was over. An eleven-year-old boy has to bring more than expensive jewelry to keep a teenage girl happy.

Here I learned other lessons of life: Work serves money, money serves love; wonderful things may not last, but you’ll survive.

Mom and Dad made a critical decision in the spring of 1948. The Los Angeles public schools were rumored to be “infested with a foreign ideology” – teachers indoctrinating elementary school students to be socialists. A change was necessary. Directly across our street was a Roman Catholic school, Saint Gregory’s. But Saint Gregory’s did not accept students who were not Catholic. So I was enrolled at Saint Thomas, miles away, and walked to catch the big red street car. I was the only kid enrolled in the fourth grade who came from outside that parish, a Presbyterian among the Catholics.

Although the transfer to Saint Thomas was intended to escape “foreign ideology,” it achieved a different result. By age twelve I was learning about justice, fortitude, courage, and hope from women and men committed to those virtues. The decision to enroll me at Saint Thomas set a course in my education that continually connected me to people involved in charity, justice, and freedom movements – selling candy to raise money for Catholic Charities, collecting food and clothes for a family whose house had burned, aiding workers on strike, or marching for civil rights. Academic subjects blended with discussions and debates about theology and social action.

A career is shaped and changed over a lifetime by many, often small, unforeseen events. “A fool sent to Rome …”

Retirement

“Retirement” is an opportunity to give unique attention to the sharing that is a life. Since my colleagues celebrated the availability of my office, and the attention of a half dozen squirrels, Mary Jane and I have had more time to visit, eat, and travel without any sense of urgency. Our daughters have sensed the change in family rhythm and visit regularly, even as the granddaughters have entered early adulthood and have careers of their own. Time spent with friends is now more focused and based less on conversations while going elsewhere.

“Retirement” is customarily used in reference to paid employment. The values of a lifetime abide. Today, like most in the last sixty years, is something of a “busman’s holiday.” I am still involved at Colorado State University with thesis and dissertation committees. I meet and opine with colleagues about the state of university education and the world; refer students to sources of current and historic information; and occasionally help someone find employment. I enjoy receiving news about how people are changing the world, and how the world is changing them.

The priority of social justice and social change burns hot as ever. I am more alarmed than ever that – justice and change – are used to exploit and manipulate. Many of us receive multiple solicitations each week asking for money to achieve justice and change without ever examining the causes of “the cause.” That is one of the glories of living in our society. My current cause celebre is the betrayal of the mission by institutions.

Since leaving classroom teaching, I have been invited to help in several quixotic projects involving groups of people wronged by organizations that claim to be their benefactors. My role has been to support situational analysis, and be a resource to recognize people’s dignity and rights, value their strategic insights, and focus their courage. The invitations have come from neighbors suffering in traditional areas of oppression – mistreatment based on diversity and access to housing and other resources.

Those projects have been Quixotic because, though successful in rallying the hope and salvaging the quality of life of the participants, they have failing to increase the vitality of arrogant and sclerotic organizations, and advance institutional growth. But that incrementalism is part of the discovery process in social justice. It requires continual renewal.